It took a scientific study from Monash University in Australia to prove that the rain water that the inhabitants of the city of Adelaide were collecting from their decks was suitable for human consumption despite not having any treatment before being consumed. Adelaide, the fifth most populated city in Australia is consuming the water from river Torrens faster than it is capable of generate it and the continuous droughts are prompting the survival instincts of its people, who have begun to recover the human tradition of collecting and storing water during rainy months.

The study took a sample of 300 households consuming untreated rainwater, analyzing their gastrointestinal health during the period of a year to compare it later to a sample of households consuming running water. The result appeared in the leading media of the country and revealed what many had suspected, “Rainwater is potable!”

Traditionally, cultures with water scarcity are those who have developed the most advanced storage technologies. In our country we have a great legacy of vernacular water engineering that comes from the knowledge exported by the descendants of the Berber ethnic, who at different times in history, entered the Iberian Peninsula and the Canary islands, building large water management infrastructures.

The Arab people took the worship of water to its best incorporating it into the design of their homes, gardens and cities, not only as a mean for everyday life but as a decorative and audible resource that became an indissoluble element of its architecture. Undoubtedly, the best known architectural heritage of water is the of the Alhambra fortification built by the Nasrid kingdom, but the foundation of Madinat Garnata, -the current city of Granada- had begun centuries before with the urbanization of the Albaicín district by the Zirid dynasty.

This settlement, whose origins date back to Roman times, remained abandoned for centuries, until around the year 1020, the Zirids founded the Alcazaba Cadima, a fortress city located in the top of the hill where today stands the Albaicín. Its inhabitants, descendants of Islamic settlements in North Africa, were able to overcome the rain shortage by taking advantage of the water run-off from the Penibetic mountain chain –where we find the Sierra Nevada-. They built a network of canals that would multiply with the growth of the population and whose water was led by gravity to the urban storage tanks: the wells –aljibes- located near palaces and mosques.

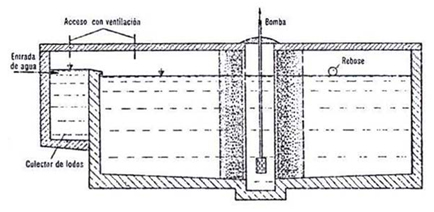

The Granada reservoirs or aljibes were half-buried and its structure, that could be made either by bricks or stones, was joined together by lime mortar which covered also the inside walls to help purify the water.

Image: Aljibe of Santa Isabel of Los Abades. Image by: Fundación El Albaicín of GranadaThe inhabitants of the Albaicín enjoy today of a clean water supply through a sourcing network inherited for nearly a thousand years of history. In 1994, following the Declaration of the Albaicín district as Unesco World Heritage Site, it was created the Albaicin Foundation which is currently responsible for the conservation of the reservoirs and the rest of the architectural heritage.

But the Berber people, from which descended the conquerors of Granada, had left long before the confines of Africa. Archaeological remains have been found indicating that a group of Berber aborigines were settled on the island of Lanzarote around 500 BC, coming from North Africa.

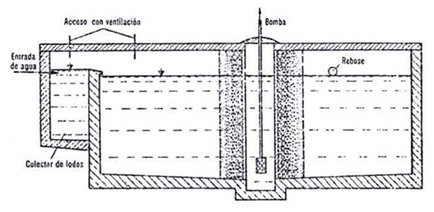

These first settlers of the island began the construction of what we know as maretas, a series of reservoirs excavated directly under the mountain to obtain water by filtration. With the arrival of the Spanish conquerors in 1402, those reservoirs were improved and new maretas were built. People started building water management systems in their own homes, so that the water collected from the roof was conducted along a natural filtering system through volcanic rock and autochthonous shrubs to be stored in reservoirs.

However in the mid-twentieth century, with the construction of Europe’s first desalination plant in the island, traditional systems of water management began to fall into disuse, hoping that the new technology would supply the water needs of the inhabitants.

But unlike the Albaicín, Lanzarote had to cope with the arrival of the tourist boom, which since 1960 had increased the population of the island until become nowadays, the Spanish region with the fastest growing population rate, even doubling its population in the last ten years. This transformation is linked to the economic growth and therefore doors have been opened to major tourist residential complex without capping the increase of energy demand and water supply.

In just 50 years, Lanzarote has built up to four desalination plants whose energy comes from the millions of gallons of oil that reach the island by sea every month. But as we know, no system can grow indefinitely in a finite planet and at some point the growing demand collapses the system. Last April, Lanzarote was declared in state of water emergency and approved urgently, the construction of a new desalination plant avoiding the mandatory environmental impact study due to the pressing need for more water.

While resorts and public water managing companies argue about who should pay the water bill, municipalities are beginning their path to a renewable energy supply, not dependent on oil, such as geothermal energy. But we must remember that sustainability doesn’t mean to generate all the energy we got from oil by natural resources. It is necessary to reduce the demand in order to create a sustainable model which strikes a balance between production and consumption.

Maybe it’s time for Lanzarote to rethink its urban policies and require to apartment and hotel developers a self-management of their water and energy consumption without waiting for the public system to supply it.

For thousands of years the Berber people have lived in our country without oil dependent technologies for generation of water resources and their population grew as much as the available resources allowed them without the need of mortgaging future generations.

There are 1,200 million of people in the planet with no access to safe drinking water and this number is expected to increase with the climate change effects. But it seems that a part of the planet doesn’t consider necessary to limit the use of resources and continues –isolated from reality- proud of their freshwater swimming pools in front of the sea.